What Larry Householder can expect in FCI Elkton

A longtime Hell's Angels member details life inside the low-security prison where Householder is slated to spend the next 20 years of his life.

Former Ohio House Speaker Larry Householder probably didn’t wake up one day and decide to participate in the biggest bribery scheme in state history (that we know about).

He had participated in the upper echelon of Ohio politics for so long that a $1 billion bribery scheme involving $250 million in political bribes seemed like a simple political ploy.

And you know what? Householder would have gotten away with it had the meddling FBI not stumbled ass-backward into the case via an already open investigation into the fabulously corrupt super-lobbyist Neil Clark, who would later die by suicide while wearing a “Mike DeWine for governor” shirt before seeing his day in court.

Anybody reading this deranged newsletter probably knows what happened next: Householder decided to roll the dice with a clown show of a defense team against the federal government and its 99 percent conviction rate. He even took the stand in his defense, and the results were predictable.

The judge stroked Householder with a maximum 20-year sentence. After being processed into the federal prison system, Householder arrived last week at FCI Elkton, a low-security prison in Lisbon, Ohio.

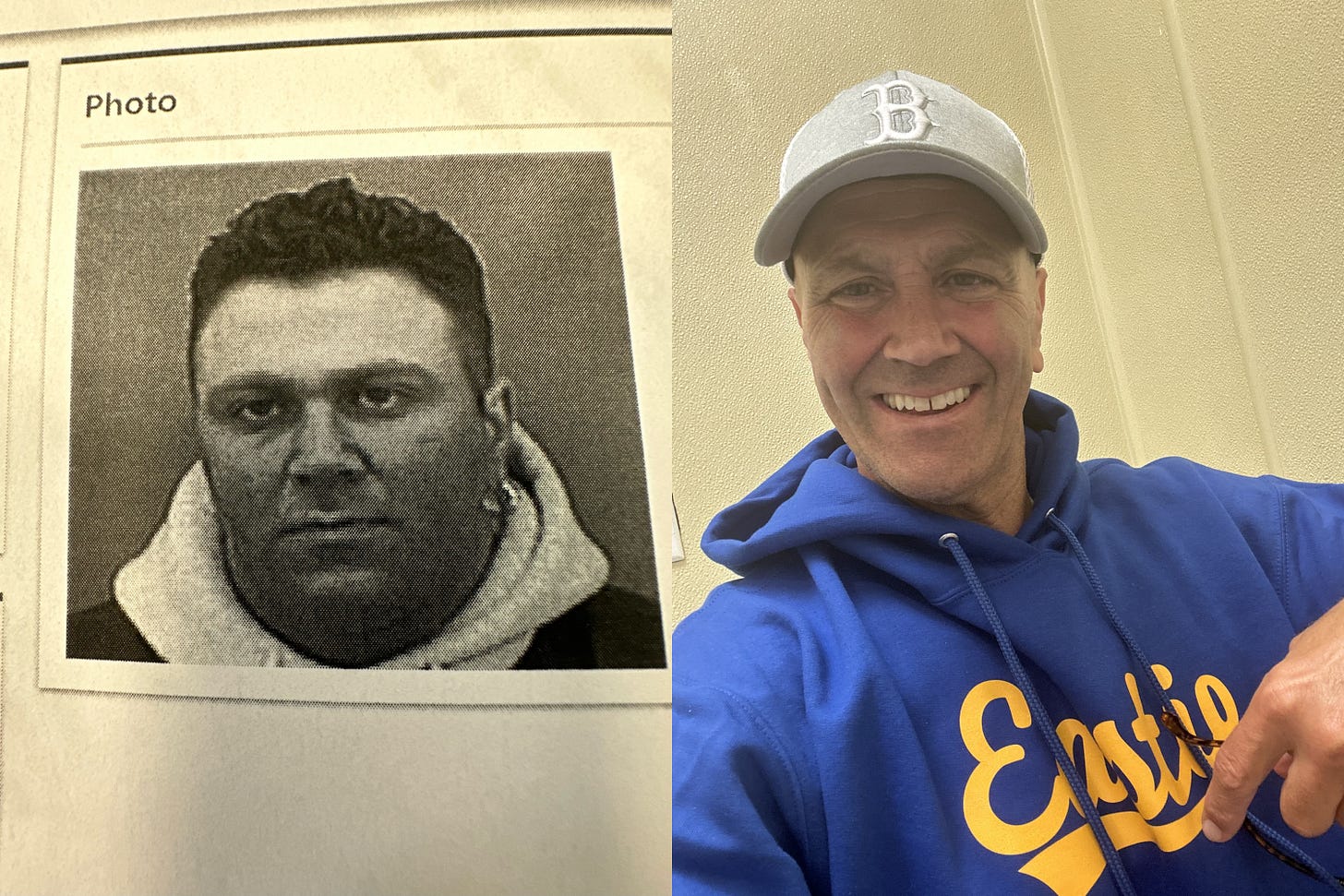

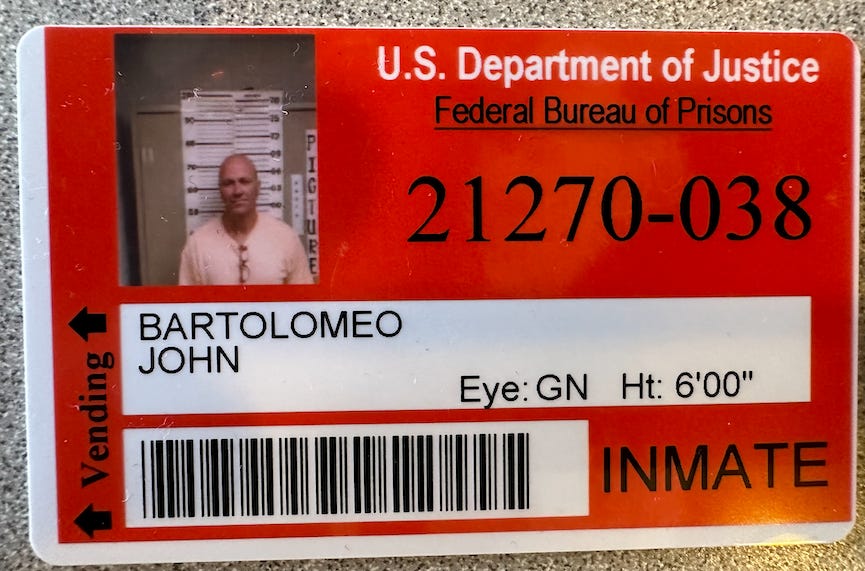

To get an idea of what Householder faces in his new life, I talked to longtime Hells Angels member Johnny Bartolomeo, a Boston native whom the federal government once sentenced to 35 years in prison for the murder of a rival gang member.

Having served his time at almost every level of security in the federal prison system, Bartolomeo painted a picture of FCI Elkton opposite of the country club prisons Americans usually envision for white-collar crooks like Householder.

Bartolomeo earned his nickname — “Johnny Bart” — not in his criminal dealings with the Hell’s Angels but as a hockey-loving youth in Boston. As you might imagine, the name Bartolomeo is a bit of a mouthful to yell multiple times during a game for a player who was “pretty decent” by his own assessment.

When asked how a kid like that ended up in the Hell’s Angels, Bartolomeo cited a childhood infatuation with motorcycles that started with him “making motorcycle sounds” while running around the house. There was also his environment.

Bartolomeo grew up in East Boston in a predominantly Italian neighborhood. He considered the mafia as “not really his thing.” The Hell’s Angels, unlike the mafia, were on the ascendency. And that intrigued him.

“It was something I wanted to be a part of,” Bartolomeo said.

Bartolomeo arrived in prison in 1996 after taking a plea deal to keep friends out of further trouble.

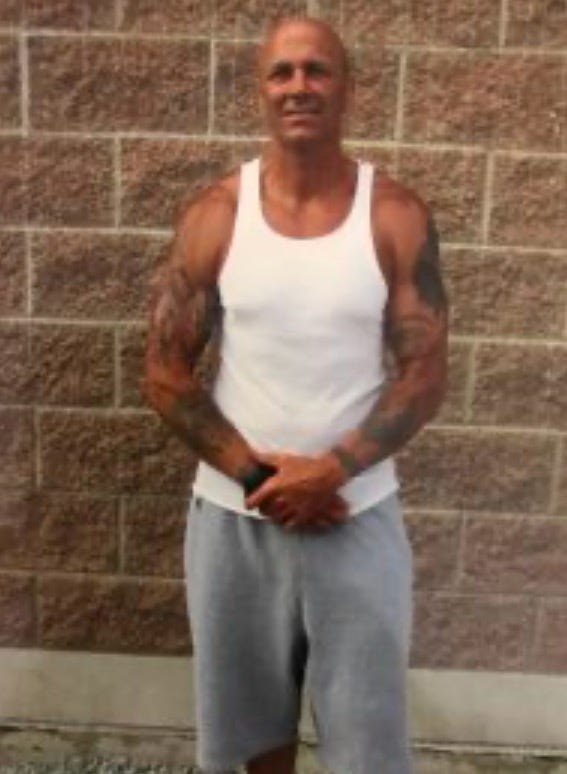

He credits his early release after 27 years — he spoke to The Rooster from a halfway house in Boston — to his ability to keep his head down, exercise every day and learn as much as possible. As Malcolm X said, prisons are second only to college campuses as places to learn.

To give you an idea of what Bartolomeo’s life could have been like had he not pursued a criminal career that culminated in him murdering a rival drug dealer, Bartolomeo taught himself Spanish in prison and is fluent to the level that he constructed courses for other inmates.

Not that his road to rehabilitation through 12 federal institutions came easily.

“I’ve seen stabbings. I’ve seen murders. I’ve seen vicious assaults,” Bartolomeo said.

“I’ve seen a lot of things that would shake your core, and the only thing you can do with them is witness and experience them… When I say I made it out of there, you never know what tomorrow brings.”

Ironically, Bartolomeo stated he preferred life in penitentiaries and medium-security camps to low-security prisons like Elkton. He said the overcrowding of low-security prisons led to more violence, particularly during the pandemic.

“Make no mistake about it. You can get your head bashed in a low-security prison… There’s always a threat of violence in low-security prisons because there are a lot of people,” Bartolomeo said.

“The [low-security prisons] to me were the worst because they were so overpopulated. … At Elkton, ten people died during COVID, with seventy people in outside hospitals. That’s a whole ‘nother thing. … When I seen all these people coming out, from all different locations—from the blocks, from the rec, from the RND, from the mailroom, from the library, from the chow hall—it was oppressive. Even a guy like me would have an anxiety attack.”

The overcrowding can breed a special kind of petty hatred for your fellow prisoners.

“In that environment, that’s all you have. Your whole life is that environment. You’re there 24/7 with people,” Bartolomeo said.

“You see them every single day. You stand beside them and urinate. You defecate in the stall next to them. You watch them brush their teeth. You hate everything about them basically because you’re with them 24/7. It never ends. The animosity toward people is magnified.”

Bartolomeo described life at Elkton like any other prison—steeped in violent hierarchy, respect and paranoia.

“That’s all it is. Politics. It’s all politics,” Bartolomeo said. “There’s politics at every security level. There are a lot of politics in low-[security prisons], in medium-[security prisons].

Bartolomeo described how “cars” — a prison term for how we use the word “cliques” — run the prison.

“It’s really about geographical areas. That’s basically how that jail runs. There’s a Mexican car. A lot of Mexicans there. There’s a guy who runs a Cleveland car. A guy who runs a Columbus car. … There’s a whole bunch of Gangster Disciples there. … A lot of gang members there.”

And if a prisoner doesn’t respect the hierarchy?

“There are grave consequences if people don’t act respectfully or do what they’re supposed to do.”

The other problem Bartolomeo described is the number of pedophiles inside the prison.

“Half the population is a pedophile. They’re the worst people to be around. But at least you know what they are. But with having so many of them, they have their own little pedophile car. But that’s another bad aspect of being in a low-security prison. These guys surround you.”

I asked Bartolomeo what advice he would give Householder, a 64-year-old corrupt politician who had never served a day in prison before being sentenced to 20 years on a racketeering beef.

“Don’t commit suicide. Try not to get cornered in a bathroom. Walk like you’re not scared. Walk like you own the place. But that comes with problems as well. If you walk like you own the place, somebody might call you out on it.”

Bartolomeo said Householder could also find himself in trouble if other inmates discover that, while at the height of his powers as the Speaker of the Ohio House, the FBI recorded Householder “talking like a gangster,” as Bartolomeo called it, by jovially threatening a political rival’s children.

“Obviously, it’s easy for anybody to talk, but when you get to a jail like Elkton there’s a good chance somebody may call you out on that. Then what? I’ll tell you what, lace up your boots, and get ready to go!”

Bartolomeo said that Householder’s age and lack of prison time means he won’t have many choices when it comes to joining one of the prison’s “cars.”

“This guy is 64 years old. He’s got 20 years. … It looks bleak. … I’ll give the same advice I give to everyone: Do something for your mind and do something for your body every day.”

The other advice Bartolomeo offered Householder was to hope that his fellow prisoners never find out that he informed against his co-defendants.

Whether Householder flipped sometime between his sentencing and his current predicament is one of the great political questions of our time. There is no proof that he has flipped, but in his new world, that might not matter if somebody finds a reason to find him suspicious.

“This is a small society that beats to its own drum every day. You can find something suspicious with everything. And when somebody finds you suspicious, it keeps perpetuating itself.

“‘Nobody goes to Oklahoma City [for federal prison processing, as Householder did last week] for less than ten days.’ … It can be anything. ‘Nobody goes into the counselor’s office for two hours.’ Little do they know, you got a legal call.

“So, there’s usually an explanation. But prison dramatics can take over, and prison dramatics takes on a life on its own. And sometimes there can be consequences…”

Johnny Bartolomeo currently works with Prison School, a business operated by longtime Ohio political consultant Bobby Ina that educates recently convicted white-collar criminals about what they can expect in prison.

While a complete internet presence is soon to come, you can contact Prison School through email.

The Rooster thanks Ina for the introduction and Bartolomeo for his generous allotment of time.